> From the WeatherWatch archives

Ocean and atmospheric conditions over the tropical Pacific Ocean in August 2015 had characteristics of a strong El Niño, according to a report released this week by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

The WMO said the majority of climate models and experts expect that El Niño will continue to strengthen through the rest of 2015, peaking between October and January. At its height, this El Niño could be among the top four strongest events on record since 1950, the WMO said.

The last strong El Niño occurred in 1997-98. Since then, there has been a reduction in the amount of Arctic sea ice and Northern Hemisphere snow cover, which introduces another factor in what to expect.

David Carlson, director of WMO’s World Climate Research program said, “We have had years of record Arctic sea ice minimum. We have lost a massive area of Northern Hemisphere snow cover, probably by more than 1 million square kilometers in the past 15 years. We are working on a different planet and we fully do not understand the new patterns emerging.”

“We have no precedent. Climate change is increasingly going to put us in this situation. We don’t have a previous event like this,” he said.

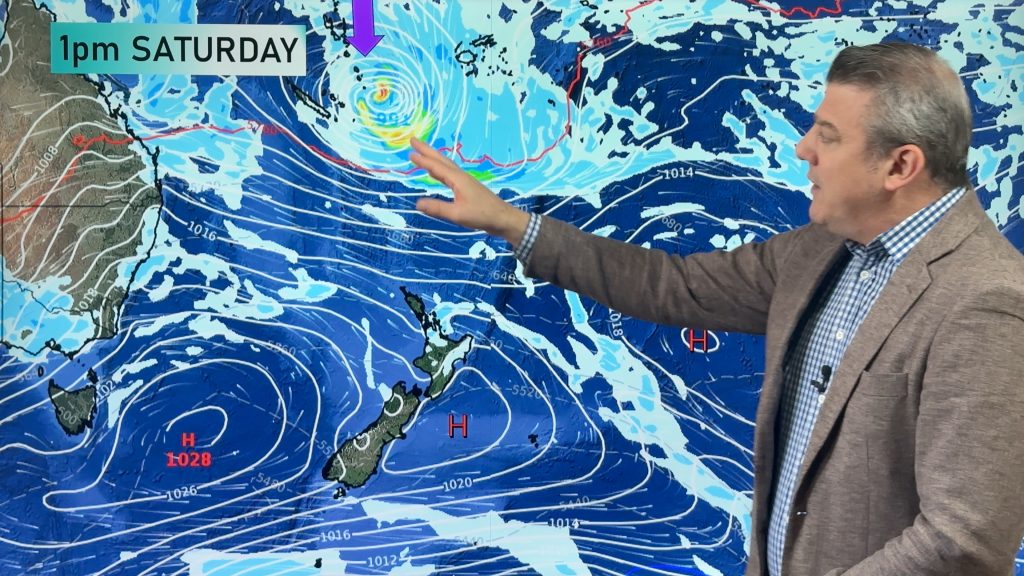

Sea-surface temperature anomalies (degrees Celsius) in the Pacific Ocean on Aug. 13, 2015. The area highlighted by the white rectangle shows the warmer-than-average waters of the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Significant warm anomalies also were present in the eastern Pacific Ocean west of California and Mexico’s Baja peninsula, while cool anomalies were seen in parts of the equatorial western Pacific Ocean. (NOAA/NESDIS)

El Niño is an anomalous, yet periodic, warming of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. For reasons still not well understood, every two to seven years, this patch of ocean warms for six to 18 months.

The fact that El Niño is likely to last into spring is important for the United States since precipitation and temperature impacts from a moderate-to-strong El Niño are typically most noticeable during the colder months. We have more on what those impacts are later in this article.

We’ve likely already seen some impacts from El Niño this summer. For example, a record number of named storms have developed during the central Pacific hurricane season – a basin where we typically see an uptick in tropical activity during El Niño. We’ve also seen strong wind shear near the Caribbean which is also typical of El Niño, and contributed to the demise of Tropical Storm Erika and Hurricane Danny in August.

The WMO report is similar to the El Niño forecast update released by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on Aug. 13. NOAA’s forecaster consensus unaminously favors a strong El Niño at its peak in the late fall and early winter.

In that forecast update, NOAA said El Niño has an 85 percent chance of lasting into early spring 2016. This is an increase of 5 percent over NOAA’s last El Niño update in July. NOAA also said that there is a greater than 90 percent chance of El Niño lasting through the upcoming winter.

NOAA reported that sea-surface temperature anomalies increased in July in the Niño 3.4 region. This is the middle portion of the equatorial Pacific Ocean that is most commonly used to measure the intensity of an El Niño event.

What does warm water have to do with your weather?

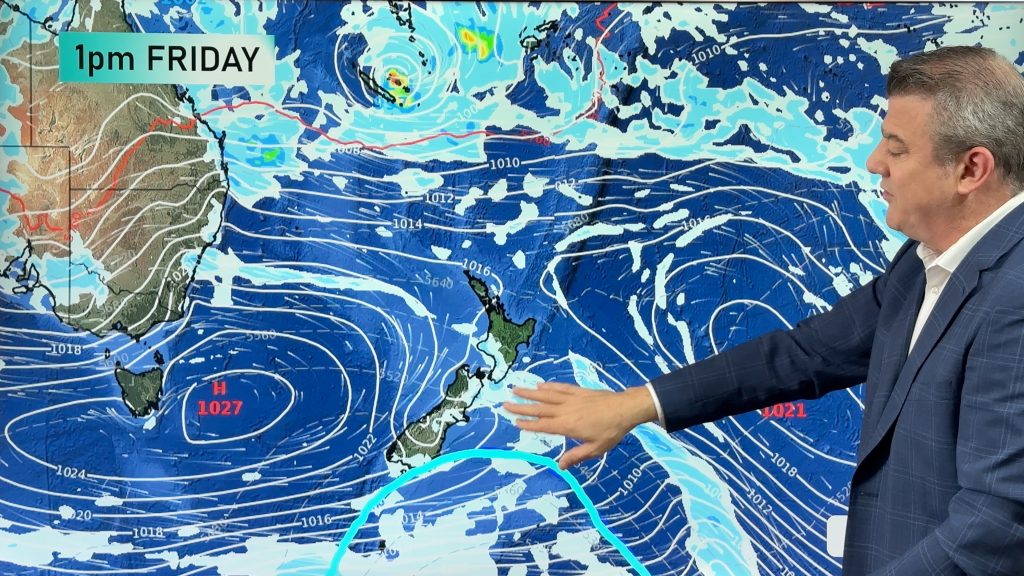

Schematic comparison of sea-surface temperature and most persistent rain/thunderstorm locations in neutral vs. El Nino conditions in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. (NOAA)

A ‘Sea Change’ in Atmospheric Circulation

Typically, easterly trade winds near the equator pile warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Conversely, the resultant upwelling, or upward movement of deep, cold ocean water keeps the eastern and central Pacific Ocean cooler.

Thunderstorms require at least some degree of warm, humid air near the surface, so they’re more numerous and persistent over the western Pacific warm pool, and much less so in the eastern equatorial Pacific.

During an El Niño, these trade winds weaken, and may at times reverse from west to east. Warmer western Pacific water then slowly sloshes back toward the central, even eastern Pacific Ocean in what’s known as an equatorial-trapped Kelvin wave.

Therefore, the most persistent thunderstorms will shift from the western to the eastern and central Pacific Ocean in an El Niño.

This trade wind reversal and the resulting reorientation of thunderstorms changes the atmospheric circulation not just over this swath of the equatorial Pacific Ocean, but can also have far-reaching impacts on the atmospheric circulation.

– Weather.com

Comments

Before you add a new comment, take note this story was published on 3 Sep 2015.

Add new comment